The Caucasus Mountains don’t hold many superlatives or titles because, compared with other major mountain chains like the Andes or the Himalayas, they’re boxed into a pretty small area. They also rise up basically straight from sea level (they border the Black Sea to the west and the Caspian to the east), so there was virtually no chance of them having the highest anything. Compare that with the Rockies—driving west across the U.S., by the time you get to Denver, which is still in the Great Plains, you’re already more than a mile above sea level! So the Caucasus range flies below the radar, but once you get yourself into the middle of it, it’s pretty overwhelming. It is a world unto itself, with all sorts of interesting secrets and idiosyncrasies. Today we’re going to focus on glaciers.

Russia owns the majority of the Caucasian range, but Georgia has quite a lot of territory in this region as well. Within Georgia’s Caucuses, there are actually 637 glaciers! That number is likely to start going down in the coming years, because… you know… climate change. But right now there are 637! And Western Georgia (aka Svaneti—where we are now) is the most densely concentrated area for these sleepy, icy giants. Today, we’re going to hike to a modest sized glacier just a few miles from the town of Mestia called Chaaladi (sometimes spelled Chalaati). There’s a map below to give you some context. The Google Reviews on these things crack me up 😂

Hiking To Chalaadi

Chalaadi Glacier is a day trip out of Mestia. It’s possible to walk the whole way from Mestia to Chalaadi, but of the day would be spent walking along the roadside that leads to the trailhead. Heading northeast out of Mestia, all you would need to do is follow the Mulkhra River, and you’d get there in a couple hours max. But we made other arrangements.

Our Airbnb host Dato told us that he could arrange a ride to get us from Mestia to the trailhead. We weren’t aware of a cheaper way to go about doing it, so we threw him a few Lari and he told us to be out front of the guest house at 9am the following morning. When that morning came, it turned out that our driver was Dato’s little sister and her friend, who were both around our age. They had taken the opportunity to make a day of it and hike the trail with us. I forget their names now, but the sister was… a character. She was like a literal cartoon character out of the Goofy Movie. And I say that in the best possible way! They spoke almost zero English and us literally zero Georgian but we still managed to communicate.

The ride to the trailhead took maybe 40 minutes, and in that time it really didn’t feel like we had travelled particularly far. We passed lots of people who were hoofing it to the trailhead. I made awkward eye-contact with lots of them out the window and for a moment I would feel like a lazy bum for being in a car, but that passed quickly. Whatever dude.

Hugging the banks of the Mulkhra River, we quickly approached the end of the valley. As the mountain ridges on either side of us began to close in, things began to get really pretty. Here’s a few snaps of what the horizon looked like by the time we actually arrived at the Chalaadi trailhead.

The trail began with a suspended wooden bridge over the Mulkhra River. Back in Mestia it was a formidable river, but nothing to write home about. Funny how your thoughts change when suddenly you have to walk across that same river. Now it felt like a raging torrent, but we made it to the other side in one piece. From there the hike was fairly easy. If you’re reading this wondering “yeah but how easy is it really?” — people were doing it with small children. So you can definitely do this.

Eventually, the easy well-defined trail that head led us through the forrest came to and end. The forrest fell away, opening up to the largest rock-fall area I’ve ever seen. And off in the distance, elevated, sitting in the depression between two mountain peaks, was Chalaadi Glacier. From a distance, it was difficult to get a sense of scale when looking at it, but—spoiler alert—it was huge once we got up close to it.

The path continued forward for a while, well-defined and easy to follow, but the closer to the glacier we drew, the more it turned into sort of a choose-your-own-adventure. By the time we got to the part where it was time for us to start going uphill towards the start of the glacier, it was literally just a mad scramble up a bunch of loose rocks. By this point, most groups with older and younger members had turned back. But we were all in our prime, so we made the scramble up.

We kept our eyes on the mass of white ice protruding from the rockfall hundreds of meters above, but by the time we got to the highest point that could reasonably be reached, we realized that we were actually on top of the lower portions of the glacier already. Between our feet and the glacier was a thin layer of loose rocks. In fact, at the very start of rockfall, where we had started our uphill scramble, the bottom of the glacier was poking out from beneath the rocks. Even in the midday summer Georgian sun, the glacier seemed to barely even be melting, save for a few drops of water. Do you ever stop to think how dramatic climate change must be if we’re literally melting GLACIERS? These things don’t fuck around. They put a cold icy aura out into the world so you literally can’t even get close to them without putting a coat on. Standing up there on top of this thing, we were freezing. Just a few hundred yards away it was a beautiful sunny day, but here in the shadow of Chalaadi, icy glacial winds whistled around us like a storm was moving in.

Here are some pictures of our approach across the rockfall area and climb up the foot of Chalaadi:

These pictures don’t give you much in terms of scale, so I want to call out one picture specifically because it does a good job of showing exactly how big this thing is compared to humans. Even this photo doesn’t quite capture it, because the people are in the foreground, but you’ll get the idea. Chalaadi is massive.

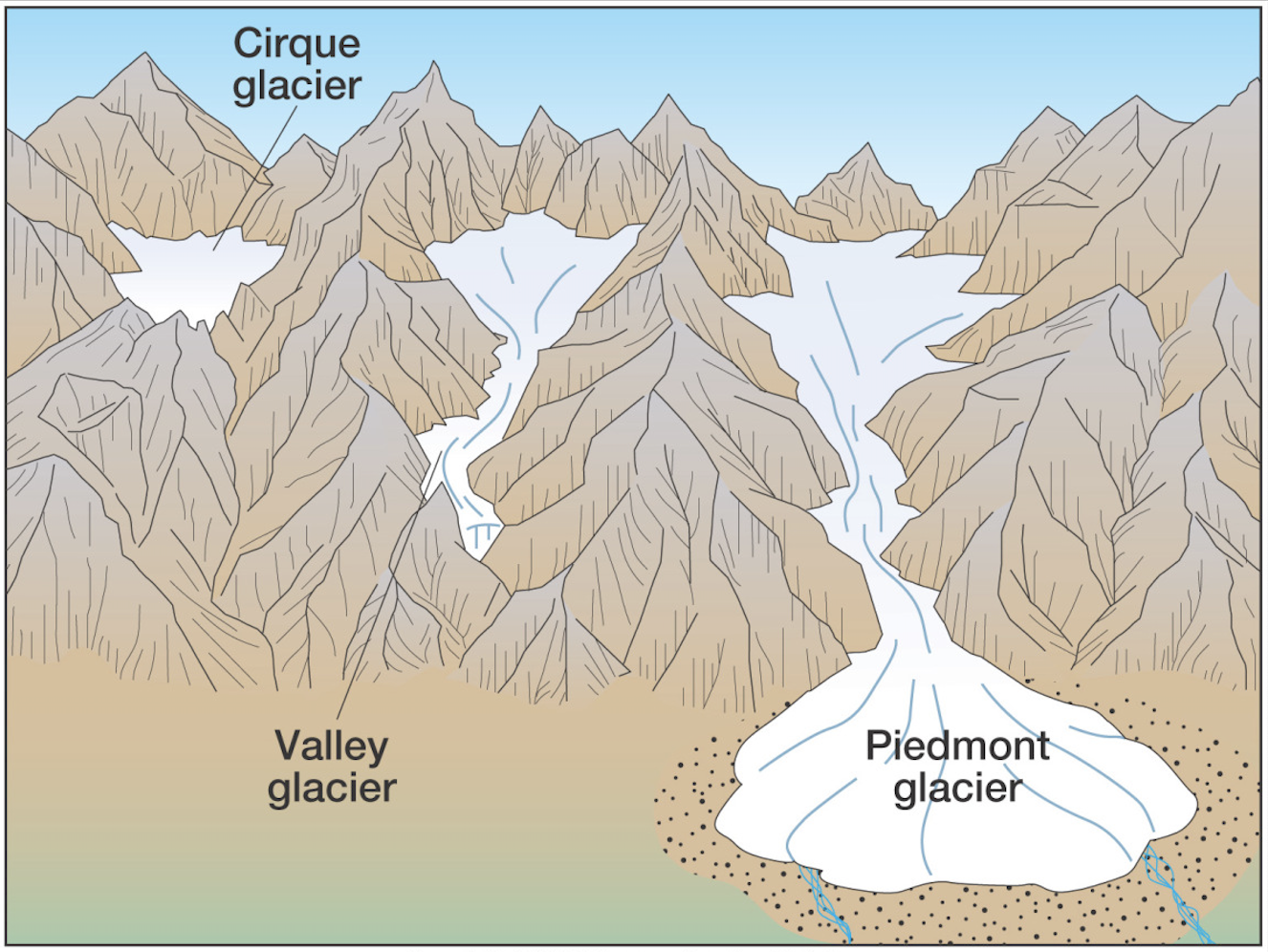

And as massive as Chalaadi is, it’s actually quite small as glaciers go. Mountain glaciers are generally of the smallest variety. And within the world of mountain glaciers, Chalaadi’s classification of glacier means that it’s only middle of the road in terms of its size. You see, this is a “Valley” glacier. There’s a whole class of glacier above this called “Piedmont,” which I have only had the pleasure of seeing once, in Iceland. Or maybe I technically saw glaciers here that wouldn’t even fall into the category of mountain glaciers, but there were photos I took of them in the linked article that definitely look like the picture below. So here’s a graphic breaking down the different tiers of glaciers that can be found in the mountains.

It’s sad to think that I might be one of the last generations that gets to see things like glaciers. I’m not sure if or when I’ll have children, but it’s a distinct possibility that many of the glaciers I’m seeing now as a young person will be gone by the time they’re old enough to appreciate them. Looking at it like that, I count myself lucky to be living through the last days of the Garden of Eden. I don’t want to sound defeatist—it’s not too late for us to course correct!—but I very much doubt that earth will re-generate its glaciers after we do. I’m not a scientist… but 🤷🏻♂️

Up next is our LAST article from Georgia—we’ll see another glacier from a distance, but mostly we’ll be focusing our time on the little-known slice of paradise known as Ushguli. I’m really excited to finally be publishing all the photos I took there!